I am also browsing a great deal of history while distracted. Last week I started reading about the hyperinflation of Germany’s currency between World War 1 and 2, a careful manipulation which allowed it to come out ahead of other countries’ economies while paying off crippling debt.

While reading about the fall of Rome, in the years 300-500 AD, I came across this: (link to original article)

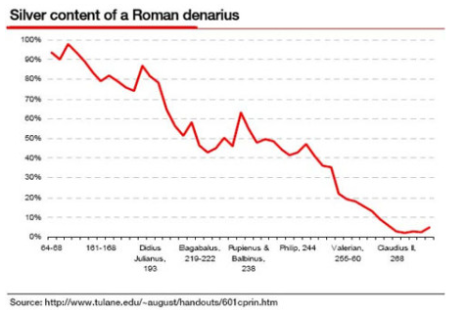

THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN DENARIUS

For hundreds of years, the Romans were on a bimetallic standard, not unlike the currency system of the early United States. There was a gold coin, the aureus, which was popularized by Julius Caesar. There was also a silver coin known as the denarius, which was what most Romans used in their day to day transactions. It was on a solid gold and silver standard that Rome ascended to the height of its development and power.

When Julius Caesar first began minting large quantities of the aureus it was 8 grams of pure gold. By the second century it had declined to 6.5 grams and at the beginning of the fourth century it was replaced by the 4.5 gram solidus. The purity of the coin itself was never debased, but the ever decreasing weight was a sure sign that government spending had been outpacing revenues for centuries.

All of this however, pales in comparison with the devaluation of the denarius.

The denarius was the backbone of the Roman economy. Citizens earning their income in gold were a rarity given that a day’s wage for an average labourer at the time is estimated at a single denarius. Thus it also became the target of severe abuse by the Roman authorities.

The denarius began as a 4.5 gram silver coin and had stayed that way for centuries under the Roman Republic. After Rome became an empire, things began to turn sour for the denarius and, by extension, the Roman economy. Base metals, such as copper were blended in with the silver and so even though the coin itself weighed the same, the amount of silver in it became less and less with each successive emperor.

Throughout the first century the denarius contained over 90% silver but by the end of the second century the silver content had fallen to less than 70%. A century later there was less than 5% silver in the coin and by 350 AD it was all but worthless, having an exchange rate of 4,600,000 to a gold solidus (or nearly 9 million to the original aureus).

… as the denarius was debased, Rome became an economic basket case. Desperate times called for desperate legislation as the fabric of society was slowly torn apart by inflation.